#68 Sleep for ICU Clinicians

On this week’s BONUS episode of Critical Care Time, Cyrus & Nick flip the coin on sleep and discuss the importance of sleep for those of us that have to work nights. We also discuss how to find ways to still get rest even when your whole world is flipped upside down! Be prepared to keep taking excellent care of your patients using some of the tricks we review here. Give it a listen - or a watch and let us know what you think!

“I am inclined to think that night is the best time for thought.”

Upside: Why work nights?

People get sick 24/7, especially in the ICU.

Working nights in the ICU has several advantages:

More undifferentiated illness → Greater diagnostic challenge and cognitive engagement

More procedures → Higher procedural volume and autonomy

Less backup → Increased independence and decision-making authority

Outstanding teaching environment → Fewer distractions, more bedside reasoning

Higher compensation / fewer shifts → More total time with family and life outside work

Less administrative burden → Less paperwork, fewer insurance battles, more actual medicine

Downsides of night shifts

There are several well documented risks of night shift work.

1. Motor Vehicle Accidents

According to National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH):

Sleeping 6–7 hours/night → 2× risk of sleep-related crashes

Sleeping <5 hours/night → 4–5× risk

The American Nurses Association (2011) reports that 1 in 10 nurses reported a fatigue-related car accident

2. Medical Errors

There is a very real risk of errors related to fatigue, which may be more common at nights.

Landmark intern-work-hour trials trial found that 24+ hour shifts were associated with higher error rates than shorter shifts. However, the results are inconsistent and highly dependent on system factors:

Quality of handoffs

Staffing

Access to overnight pharmacy support

It’s unclear how much of the added risk is from working nights versus working extended duration (>12 hour) shifts.

Key point:

Sleep deprivation matters—but so does how night work is implemented.

3. Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

A meta-analysis of mostly low-quality studies suggests:

Preterm delivery: OR 1.21 (95% CI 1.03–1.42)

Miscarriage: OR 1.23 (95% CI 1.03–1.47)

4. Cardiometabolic Risk

Night shift is associated with:

Impaired glucose tolerance

Reduced insulin sensitivity

Higher BMI

UK Biobank data:

Regular night workers → 16% higher risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity

≥10 night shifts/month → even higher risk

Risk amplified in morning chronotypes

5. Cancer Risk (Complex and Controversial)

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies night shift work as Group 2A (“probably carcinogenic”) exposure. However the evidence for carcinogenic effects of night-shift work are dubious:

Breast cancer data:

Case-control studies: weak positive signal

Large prospective studies: mostly negative

Nurses’ Health Study I: signal disappears with longer follow-up

Million Women Study (UK): no increased risk

Takeaway: If a signal exists, it’s small, confounded, and only seems to be present in methodologically weaker studies.

6. All-Cause Mortality

A meta-analysis of 17 studies found a slightly increased risk of all cause mortality among night shift workers:

RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.99–1.06)

Conclusion: Tiny individual risk, however a potentially meaningful population impact. We need to do everything we can to make night shifts safer.

How can we make working nights better and safer?

Between 9 and 15 million people work night shifts in the US. Healthcare depends on 24/7 staffing.

Working nights means fighting biology, and biology usually wins if we don’t adapt intelligently.

What can we do to make this safer and better for night shift workers?

1. Chronotype Matters

Unsurprisingly, people with an evening chronotype may tolerate working nights better

Sidenote: a Meta-analysis found a (small) association between evening chronotype and greater intelligence; so is it smart to work nights?

How can I tell what my chronotype is?

Circadian Type Questionnaire (CTQ)

2. Short sleepers may do better at nights

Sleep requirements

In part one, we talked about how the average sleep required is 7-8 hours with a standard deviation of 1 hour.

Night shift may be better suited for people on the lower side of that.

People who need >8 hours of sleep may be less well suited to nights.

3. Optimizing Life on Nights: Non-Pharmacologic Strategies

The goal is reversing or blunting circadian signals.

Light

Blue light strongly suppresses melatonin

Before work:

Bright, blue-spectrum light exposure

After work:

Sunglasses, hats

Avoid morning sun

Consider blue-blocking glasses late in shift

Evidence:

Blackout blinds → ↑ melatonin, ↓ sleep latency

Eye masks → ~15% ↑ total sleep time

Daytime light exposure delays sleep onset

Sleep Environment

Dark, quiet, cool room

Ideal: 16–19°C (60–67°F)

>24°C → worse sleep efficiency

Depending on preference consider using:

Earplugs

White/pink noise

Sleep Timing

Gradually delay sleep before nights

Gradually advance sleep after nights

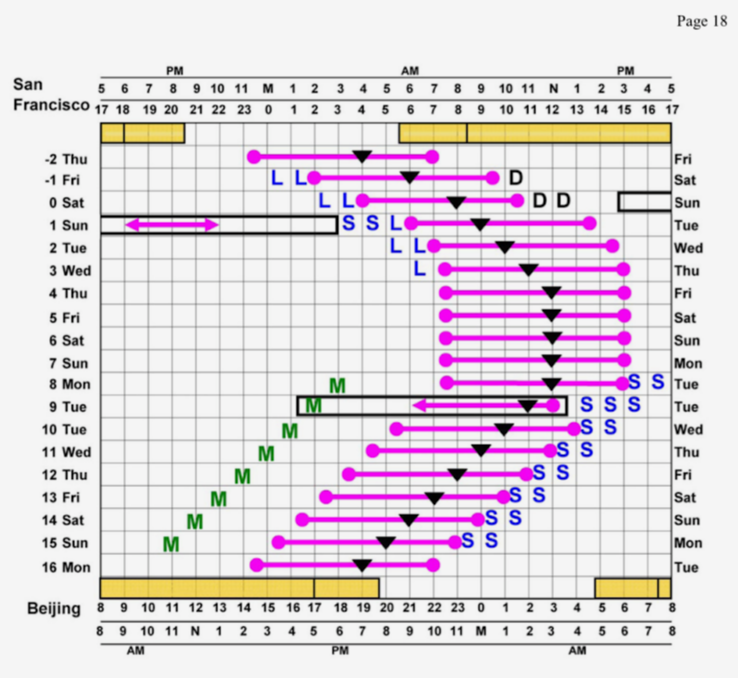

Example from the excellent article “How to Travel the World Without Jet Lag”:

S denotes sunlight exposure and L denotes exposure to a lightbox. D indicates when to avoid sunlight exposure.

M denotes low dose melatonin (0.5 mg)

Exercise

Exercise is another important zeitgeiber.

The timing of exercise is just as important as the type.

On nights: late afternoon / after waking

Returning to days: morning exercise

Evidence:

Improves alertness

Reduces fatigue

However, exercise after shift worsens sleep latency!

Meals & Chrono-Nutrition

GI tract has its own circadian rhythm

Glucose tolerance is worst at night

Nighttime eating worsens metabolic outcomes

Also changes in endocrine hormones can worsen or improve sleep and wakefullnes.

Evidence highlights:

Daytime-only eating preserves glucose control

A RCT of firefighters working 24-h shifts found that a 10-h time-restricted eating (TRE) window for 12 weeks was feasible and improved several cardiometabolic endpoints and quality of life versus usual intake.

Emerging data: fasting or light snack overnight better than full meals

Practical strategy:

Don’t fully flip meal schedule

Avoid heavy meals after midnight

Nick’s routine:

Wake → exercise

“Dinner” with family (biologic breakfast)

Light meal at work (10–11 pm)

Optional small snack (2–3 am)

Banking Sleep

Banking sleep is defined as “the proactive, short-term practice of increasing sleep duration (e.g. 1–2 hours extra) in the days prior to anticipated sleep restriction to mitigate fatigue and improve cognitive performance, alertness, and mood“

Evidence suggests this is one of the most effective performance strategies for residents working night shifts.

Essentially, you increase sleep before beginning night shifts and shift bedtime later in advance. Practically this means stay up late and sleep in before before beginning some night shifts.

Strategic Napping

Strategic napping is defined as “a planned, short-duration sleep period (10–30 minutes) designed to combat fatigue, boost alertness, and improve cognitive performance“.

Several studies support strategic napping:

An ED study of nurses and physicians found that a 40 minute nap at 3am, improved cognitive performance up to 7am in clinicians working 12 hours shifts.

A study of night shift aircraft mechanics found that taking a single 20-min nap during the first night shift significantly improved speed of response on a vigilance task measured at the end of the shift compared with the control condition.

A systematic review concluded that “Brief duration naps (≤30-min) can improve sleepiness and/or fatigue while reducing the risk of impaired post-nap performance and should be considered when performance is critical within the first 60-min post-nap”

Additionally the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recommends brief naps when performance is critical.

Practical guide to strategic napping:

Overcome stigma: Many clinicians feel bad about “sleeping on the job” but strategic napping during periods of “down time” likely improves cognition, enhancing patient safety. There’s nothing shameful about recharging so you can keep patients safe.

Set aside time for rest whenever possible: Let colleagues know where you will be, how long you (hope) to nap for, and how they can get a hold of you if needed urgently.

Don’t overdo it: Try to sleep 20-30 minutes between 3-4 am. Sleeping earlier or for much longer can paradoxically increase fatigue.

4. Pharmacologic Strategies (“Better Living Through Chemistry”)

Caffeine

Caffeine is the most widely used psychoactive drug on Earth.

Caffeine is a an adenosine receptor antagonist. It works by preventing the neurotransmitter adenosine from binding to its receptors, which in turn reduces sleep pressure, increases neuronal activity, and enhances dopamine signaling — key for improved focus and cognition.

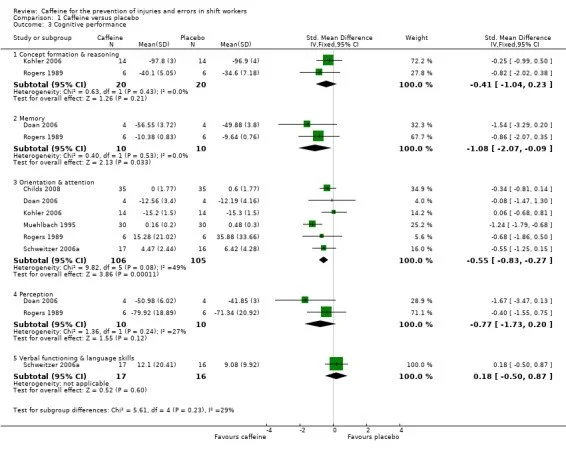

A Cochrane Review demonstrates that caffeine improves reaction time, vigilance, physical performance in shift work. It also reduces the occurence of errors in many different contexts (such as driving, flying, and medical work)

Caffeine enhances performance at least as much (and potentially more) than naps.

Challenges of caffeine —> dosing/frequency need to be personalized.

Half-life variability: 3–6 hours (most people); certain medications (fluoxetine) or physiological states (pregnancy) can dramatically prolong half-life.

Genetics matter: CYP1A2 polymorphisms: Fast metabolizers (AA) tolerate more caffeine and benefit from higher doses. Slow metabolizers (CC) may experience anxiety and insomnia at modest doses.

Properly Dosing caffeine

Military/NASA-informed approach:

Strategy: Front-load caffeine, avoid caffeine during the last 6 hours before sleep

Example strategy:

200 mg at shift start

100 mg every 2–3 hours

Stop ≥6 hours before planned sleep

If you are a fast metabolizer - either because you did 23andMe or because you have just found this out empirically - you could consider higher doses and continuing a little later into the shift.

Creatine

Buffers ATP via phosphocreatine; like caffeine this has the effect of reducing adenosine levels, which reduces sleep pressure and enhancing performance.

Like caffeine, there is some evidence that creatine improves cognitive performance during sleep deprivation. However the data is much more limited.

Data:

Small trials, mostly in athletes

Most found performance benefits with chronic use (3–5 g/day), one small RCT found that a single large dose (~30 g) enhanced night time performance

Summary:

Like caffeine - and possibly by a similar mechanism - creatine may enhance cognitive performance and prevent fatigue.

Optimal dosing schedule is uncertain.

Melatonin

Pharmacology:

Melatonin is an endogenous hormone secreted by the pineal gland, acting as a key chronobiological regulator of the sleep-wake cycle by signaling darkness to the brain. It binds to MT1 and MT2 receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), decreasing neuronal firing (promoting sleep) and shifting circadian rhythms (phase shifting).

In other contexts, Melatonin is effective for treating insomnia, jet lag, and delayed sleep phase syndrome, with limited side effects.

Melatonin may be beneficial for promoting earlier sleep in night shift workers.

Half-life: highly dependent on dose!

Evidence:

Modest benefit.

One RCT in RNs found that melatonin reduced sleep latency by ~15 minutes but did not increase total sleep time

One study in ED physicians found minimal benefit to melatonin.

Dosing:

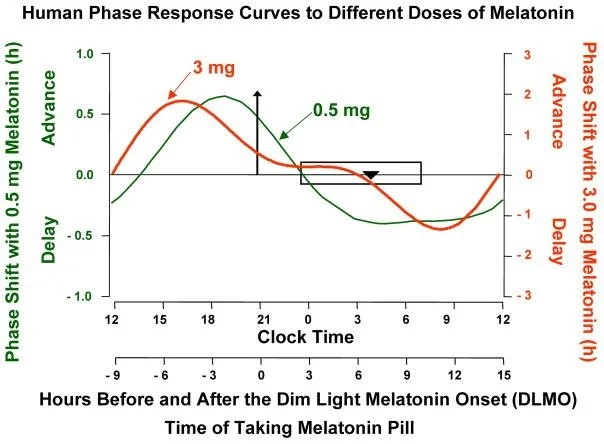

Melatonin (0.3–5mg) is recommended 3-4 hours before intended daytime sleep to help night-shift workers adjust their circadian rhythm, improve sleep quality, and reduce sleep onset latency.

Higher doses (1-5 mg) are likely to cause daytime somnolence.

Fast-release preferred; slow release forms more likely to cause somnolence after waking.

Quality concerns: a JAMA 2025 study found that

Only 12% of melatonin gummies accurately labeled

Some had >300% of stated dose

One had no melatonin but did contain CBD (bad reason to fail a drug test!)

Contrarian take:

Melatonin may be better used for phase shifting, not sleep induction. (e.g. use it as part of a sleep banking protocol)

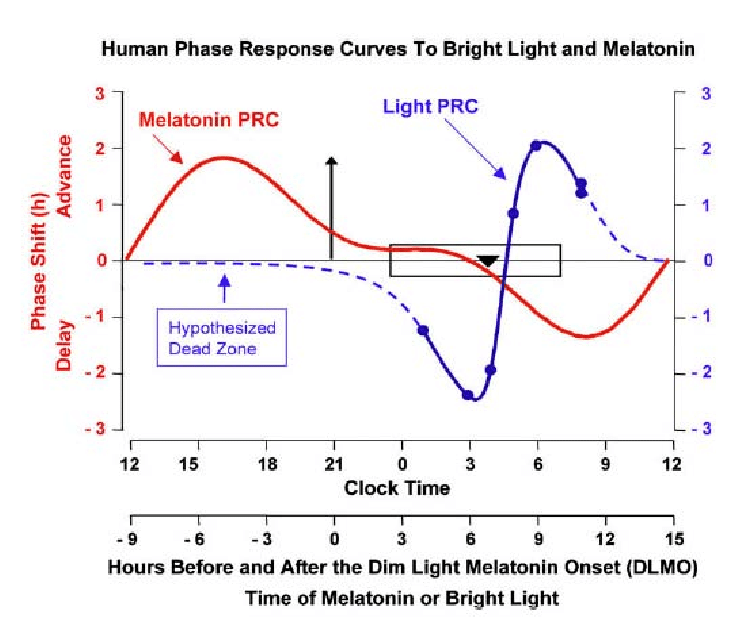

For best effects you need to correctly dose melatonin and combine with light exposure as shown below (from How to Travel the World Without Jet Lag):

Ramelteon

Pharmacology:

Similar mechanism to melatonin; ramelteon is a synthetic, selective melatonin receptor agonist (MT1 and MT2) used to treat insomnia, specifically targeting sleep onset. By acting on the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, it promotes sleep with no abuse potential, no dependence, and limited daytime somnolence.

Half-life: 1-2.6 hours

Evidence

Limited data for night-shift workers

May reduce sleep latency

Overall: Similar effects but more expensive than melatonin

Hypnotics (e.g. zopiclone)

Pharmacology

Zopiclone is a short-acting, non-benzodiazepine hypnotic agent of the cyclopyrrolone class used for short-term insomnia treatment. It acts as a full agonist at GABAA receptors, enhancing inhibitory GABAergic neurotransmission to produce sedative, anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, and muscle-relaxant effects.

Half-life: 4-5 hour half-life

Evidence:

A Cochrane review found no consistent increase in daytime sleep duration

AASM recommendation states that hypnotics (including zolpidem) may be indicated to promote or improve daytime sleep in night-shift workers; however, they do not reliably improve on-shift alertness and should be used as part of a broader plan (light control, naps, caffeine timing, scheduling).

Overall: probably not a great or sustainable long term solution to working nights

Stimulants (Modafinil / Armodafinil)

Pharmacology:

Modafinil is an atypical, wake-promoting CNS stimulant used to treat excessive sleepiness by increasing alertness without the high addiction potential of traditional stimulants. It primarily functions as a weak inhibitor of the dopamine transporter (DAT), raising extracellular dopamine levels. It also indirectly elevates norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine, and orexin, particularly in the hypothalamus and prefrontal cortex.

Evidence:

NEJM trial of modafinil in shift-work sleep disorder found

Improved alertness

Reduced near-miss accidents

Did not eliminate daytime sleepiness

Bottom line: Small benefits, not a magic fix.

What Systems Can Do Better

Optimize work schedules

Fixed schdules better than rotating on and off nights.

Let people choose nights if possible

Earlier AM sign-out to avoid sun exposure (similar to casino workers to avoid going home in bright sunlight)

Encourage strategic naps (provide dark, cool, quiet rest spaces)

Don’t waste time at shift end!

Provide (free) coffee at work; something tech figured out decades ago!

Normalize sleep safety culture:

Always have available call rooms —> recovery nap before driving

Ride-home support —> pay for taxi for night shift workers who are fatigued, no questions asked

Final plea: Abolish daylight savings time. (Nick remains weirdly militant about this; see his blog post)