#67 Sleeping in the ICU: Why is it critical and how do we help our patients get more of it?

On this episode of Critical Care Time we delve into the fascinating world of sleep with a focus on the importance of sleep in our ICU patients and how we can promote good quality sleep in the sickest patients in the hospital. Try not to sleep through this one as we provide some valuable insights and high quality pearls to get you geared up and ready to be a champion for sleep in your ICU! As always, listen and let us know what you think. Special thanks to The Difficult Airway Course: Critical Care, for sponsoring this episode!

“Sleep that knits up the ravelled sleeve of care, The death of each day’s life, sore labour’s bath, Balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course, Chief nourisher in life’s feast”

Why do we sleep?

Sleep is:

Universal: Seen in all vertebrates and many invertebrates.

Conserved: Even animals under intense evolutionary pressure (e.g. prey species, migratory birds, marine mammals) still sleep — sometimes with just half the brain at a time.

Dangerous: Sleep renders one immobile, unable to forage, and vulnerable to predation - yet evolution has kept it - universally (even in birds & cetaceans, which can only sleep with half their brains at a time).

Sleep must be doing something essential.

Leading theories on why we sleep:

Sleep conserves energy and is restorative

Reduced metabolic rate and energy expenditure during sleep.

Increased growth hormone and tissue repair during sleep.

During deep NREM sleep, interstitial space in the brain expands, facilitating bulk flow of CSF through perivascular pathways (the “glymphatic” system) and clearance of metabolites like β-amyloid.

Sleep is essential for neural “maintenance” and memory

Wakefulness → synaptic strengthening everywhere.

Sleep → global “down-selection” of synapses to prevent overload, preserving only the most important connections.

Slow-wave sleep (SWS / N3): supports declarative (fact-based) memory.

REM sleep: supports procedural skills and emotional memory; adequate REM reduces amygdala reactivity and improves emotional regulation.

Sleep regulated immune and hormonal function

Sleep loss → ↑ IL-6, TNF-α, CRP; ↓ NK cell activity and impaired vaccine responses.

Sleep integrates:

Cortisol: circadian pattern; chronic sleep debt raises baseline stress tone.

Growth hormone: pulses during early night SWS; important for children, healing.

Leptin & ghrelin: poor sleep → ↓ leptin (satiety), ↑ ghrelin (hunger) → increased appetite and weight gain.

Basic Sleep Physiology

1. Brain circuits: sleep vs. wake promoting

Sleep-promoting regions:

Ventrolateral preoptic (VLPO) area in hypothalamus, others.

Wake-promoting regions:

Monoaminergic systems (reticular activating system), orexin neurons, histamine, etc.

Sleep occurs when the balance tips toward VLPO (sleep drive) and away from wake-promoting systems.

Two key biochemical signals facilitate

Adenosine:

Builds up during wakefulness as ATP is used → acts on A1 receptors → “sleep pressure.”

Caffeine works largely by blocking adenosine receptors.

Melatonin:

Secreted by the pineal gland in response to darkness via SCN → sympathetic → pineal pathway.

More of a “darkness signal” than a sedative; modest effects on sleep onset.

2. Circadian clock & clock genes

Every cell has a roughly 24-hour molecular clock:

CLOCK/BMAL1 drive transcription of PER/CRY genes → PER/CRY proteins accumulate, then inhibit CLOCK/BMAL1 → levels fall → cycle restarts in ~24 hours. PMC

These clocks are ancient and conserved from cyanobacteria to humans. PMC

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus is the “master clock” that synchronizes peripheral clocks via neural and hormonal outputs.

Suggested figure: Cartoon of the transcription–translation feedback loop for clock genes.

3. Zeitgebers (“time givers”)

Environmental cues reset/synchronize our internal clocks:

Light: strongest zeitgeber, especially blue wavelengths in the morning.

Meals: timing and size signal peripheral clocks in liver, gut, pancreas.

Activity/exercise: shifts circadian phase depending on timing.

Temperature & social cues: weaker, but still contribute.

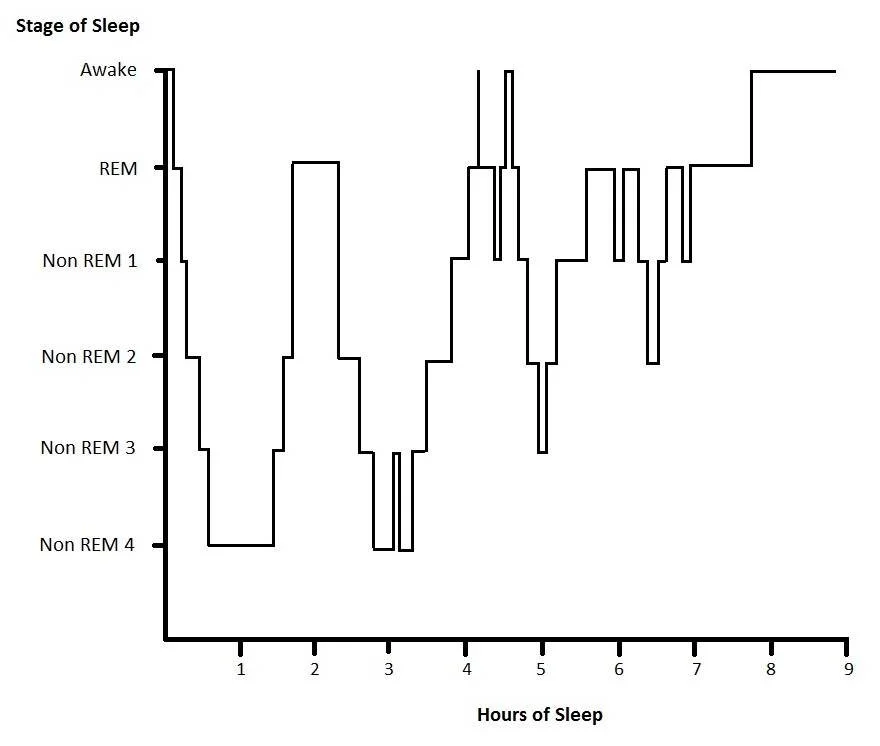

Sleep Architecture: NREM & REM

Sleep is not a single state; it cycles across a typical ~90-minute pattern:

NREM Stage 1–2: light sleep, spindles and K complexes in N2.

NREM Stage 3 (slow-wave or N3): deepest sleep; high amplitude delta waves, most restorative.

REM: rapid eye movements, low EMG tone, dreaming; brain looks “awake” on EEG.

Over the night:

First third: more N3

Later cycles: longer REM bouts, less N3

Typical hypogram for a patient sleeping outside the ICU (Source Wiki)

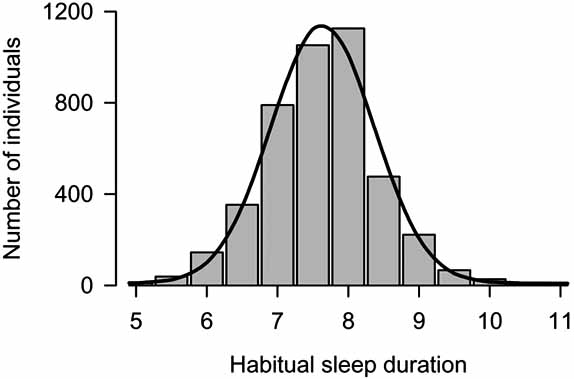

How Much Sleep Do We Need?

Population-level data:

Adults:

Mean ~7–8 hours with SD ~1 hour (most adults cluster between 6–9 h).

Habitual <6 h is associated with worse neurocognitive performance, cardiometabolic risk, and mortality in observational data.

Infants: ~14–17 h/day; teenagers: 8–10 h; older adults: often 6–8 h.

Chronotypes (“larks” vs “owls”)

Morning type (“larks”): ~25–30%

Evening type (“owls”): ~20–25%

Intermediate: ~40–50%

Twin and genetic studies suggest ~50% heritability; variants in clock genes (e.g., DEC2, ADRB1, SIK3) contribute to “natural short sleep” in about 1% of people who can function well on ~5–6 h/night.

Meta-analysis: eveningness shows a small positive association with measured cognitive ability but worse academic performance—probably because schools are aligned to morning schedules.

Source: Somehow I Manage, by Scott M et al

What Happens When Sleep Is Disrupted?

Think of sleep deprivation as a multi-system insult:

CNS & cognition: decreased attention, slower reaction time, micro-sleeps, impaired working memory, increased delirium risk.

Mood & PTSD risk: hyper-reactive amygdala, impaired emotional regulation; sleep fragmentation is linked to PTSD and depression.

Pain: disrupted descending inhibitory pathways → hyperalgesia, higher analgesic needs.

Cardiovascular: ↑ sympathetic tone, HR, BP; greater arrhythmia risk and endothelial dysfunction. PubMed

Immune: ↑ inflammatory markers (IL-6, TNF-α, CRP), ↓ NK function, worse infection outcomes.

Metabolic/endocrine: insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, ↑ ghrelin / ↓ leptin → weight gain and type 2 DM risk.

Derm/wound healing: impaired collagen synthesis, increased inflammation, hyperglycemia → slower wound healing.

Sleep in the ICU

How bad is ICU sleep?

Polysomnography and actigraphy studies show:

ICU patients often get only 2–4 hours of fragmented sleep per 24 h, with dozens of awakenings.

Sleep architecture is profoundly abnormal:

Dramatically reduced N3 (slow-wave) and REM sleep.

Many patients have “pathologic wakefulness” on EEG despite appearing drowsy.

Recent work suggests that worse sleep—especially complete absence of REM—is associated with worse ICU outcomes, including longer ventilation and higher mortality.

The 2023 ATS research statement on Sleep and Circadian Disruption (SCD) in the ICU summarizes:

SCD is common, severe, and multi-factorial

Likely contributes to delirium, prolonged ventilation, longer LOS, and impaired recovery, though causality is still being clarified.

Six Major Drivers of ICU Sleep Disruption

Light —> ICUs are bright at the wrong times

Overhead lights are often on at night; windows often covered by day.

This obliterates the normal light–dark cycle that the SCN uses to synchronize circadian rhythms.

Noise —> ICUs are loud

Continuous sounds from monitors, alarms, pumps, ventilators, phones, conversations.

WHO suggests hospital nighttime noise <35–40 dB; many ICUs are in the 60–80 dB range, (because this is a log scale, this is 10–1000× higher than goal!)

Activity & interruptions

q1 neuro checks, q2 vitals, finger sticks, freqeunt suctioning, 4 a.m. labs, 5 a.m. CXRs, baths, nebulizers, bedside discussions, etc all interrupt restful sleep.

One review estimates an ICU patient may experience 30–40 care interactions per night.

Pharmacology

Sedatives (propofol, benzodiazepines) produce unconsciousness, not physiologic sleep; they suppress REM and N3.

Corticosteroids, β-agonists, some antibiotics (e.g. cefepime neurotoxicity) can cause insomnia or delirium.

Abrupt discontinuation of home meds (e.g. SSRIs, gabapentin, dopamine agonists) can also worsen sleep.

Illness & devices

Acute pain, dyspnea, chest tubes, Foley catheters, non-invasive or invasive ventilation, pruritus, nausea—all interfere with both sleep initiation and continuity.

Psychology & unfamiliar environment

“First-night effect”: in a novel environment, one hemisphere stays more vigilant (higher arousal thresholds) as a “night watch” system.

In the ICU, patients may repeatedly experience a “first-night effect” with room moves, noise, fear, and uncertainty.

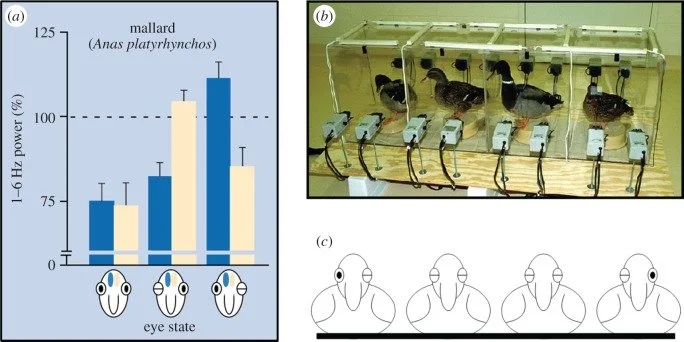

Sidebar: Unihemispheric Sleep: Not just for animals anymore?

Many birds and marine mammals use unihemispheric slow-wave sleep (USWS)—one hemisphere sleeps while the other stays awake enough to surface, navigate, or watch for predators.

In humans, Tamaki et al. showed that in a novel sleep environment, one hemisphere exhibits lighter sleep and more vigilance, consistent with a partial “night watch” effect.

In the ICU, this likely means patients are never fully “off”—even when they appear to be asleep, one hemisphere may stay on high alert.

Birds sleeping on a log maintain vigilance for approaching predators; the birds on the outside exhibit unihemispheric sleep to literally “keep one eye open.” (Source: Rattenborg, Sleeping on the wing. Interface Focus. 2017)

Improving Sleep in the ICU: A Toolkit

1. Optimize Light (Zeitgeber #1)

Goals: bright days, dark nights.

Daytime

Open shades; maximize natural light.

If possible, use full-spectrum / blue-enriched lighting during daytime.

Nighttime

Dim overhead lights; use task lights or flashlights.

Avoid unnecessary overnight TV.

Eye masks / eye shields

Multiple RCTs show eye masks and earplugs improve subjective sleep quality, double time in N3 sleep, and some show reduced delirium.

2. Reduce Noise

Keep conversations outside rooms when feasible.

Tailor alarm limits and delays; avoid “alarm fatigue” while eliminating nuisance alarms.

Patients do not need an alarm every time they fall asleep and their heart rate drops below 60 bpm!

Turn off TVs and other unnecessary audio at night.

Ear plugs:

RCTs & meta-analyses: ear plugs (with or without eye masks) increase time in N3 and may reduce delirium by ~40–50%, with a ~20–25% relative reduction in mortality in pooled analyses.

A life-saving ICU Intervention. Administer aurally. NNT = 4-5?

3. Reduce Nocturnal Activity & Cluster Care

Avoid “ritual” labs and CXRs that don’t change management; question 4 a.m. labs and daily CXRs.

Remove unnecessary devices (Foley, arterial line, NG tube, etc.) as soon as safe.

Cluster interventions: bundle vitals, labs, weights, baths into fewer interruptions.

Use “quiet hours” when non-urgent care is deferred.

Activity: Can we make our patients more active during the day?

Other environmental Considerations:

Temperature: Most people sleep better in a slightly colder environment.

Feeding: There’s some evidence that overnight feeding - like continuous tube feeds - might disrupt sleep due to higher nocturnal glucose.

4. Treat Pain, Nausea, Dyspnea, Fever

Scheduled acetaminophen often provides smoother analgesia than repeated opioid boluses.

Aggressively treat nausea, dyspnea, and pruritus.

Address ventilator dyssynchrony; consider switching to pressure support for comfort when appropriate.

5. Pharmacology – What Helps? What Hurts?

Guiding principles:

Start with non-pharmacologic measures.

If you use drugs, use lowest effective dose, shortest duration, and stop at discharge when possible.

Beware of meds started in the ICU that follow patients home—e.g., quetiapine initiated for sleep and continued indefinitely; some series suggest ~40–50% of such patients leave hospital on these meds. PMC+1

Lower-risk / first-line options

Melatonin & ramelteon

Pharmacology:

Melatonin: endogenous hormone of darkness; minimal toxicity.

Ramelteon: synthetic melatonin receptor agonist; more expensive not necessarily superior

ICU data:

Several small RCTs (ICU and peri-op) showed improved subjective sleep and decreased delirium, but two large ICU RCTs (Pro-MEDIC and DEMEL) failed to show benefit on delirium, LOS, or mortality.

Meta-analysis of 14 trials (n=1712) found reduced delirium incidence overall (RR ~0.6), but heterogeneity is high and effects are stronger in surgical than ICU cohorts.

Bottom line in ICU:

Safety: good

Efficacy: modest/inconsistent

If you use it: low dose, early evening, not at 3 a.m. “because the patient is still awake.”

Dexmedetomidine (for intubated patients)

Pharmacology:

α2-agonist sedative that more closely mimics NREM sleep than GABAergic agents.

ICU Data:

A small two-center placebo controlled RCT found low dose nightly precedex reduced delirium risk, though interestingly didn’t improve self reported sleep quality.

Another placebo controlled small study found improved sleep efficiency, more N3 sleep, and fewer arousals with dexmedetomidine.

Large RCTs (e.g., n=3000 SPICE III trial) did not show mortality benefit and raised concerns about bradycardia/hypotension at higher doses.

Practical take:

Reasonable “least bad” sedative for ventilated patients who require sedation.

Consider low-dose, night-time targeted infusions; watch HR/BP closely.

Moderate-risk / second-line options

Gabapentin

Pharmacology: GABA agonist

ICU Data:

Small ICU RCT (n≈60) showed increased slow-wave sleep (66.8 vs 0 min) and longer total sleep time (331 vs 46 min).

Also useful for neuropathic pain and RLS.

Risks: sedation, dizziness, ataxia; dose adjust in renal dysfunction.

Reasonable to restart home gabapentin or consider as adjunct for neuropathic pain; caution in elderly/frail.

Trazodone

Pharmacology: SARI antidepressant used off-label for insomnia outpatients.

Evidence in ICU: essentially absent; very limited data in hospitalized patients!

Risks: QT prolongation, orthostatic hypotension, anticholinergic effects, priapism (rare).

American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) insomnia guideline recommends against trazodone for chronic insomnia due to limited efficacy data.

Practical take: don’t use. If used, monitor QTc, BP. Many clinicians are moving away from routine trazodone for sleep.

Clonidine

Oral α2-agonist, sometimes used for withdrawal or hypertension.

Very little ICU sleep data; often thought of as “cheap dex.”

Risks: hypotension, bradycardia, rebound hypertension.

Reasonable to continue home clonidine; not ideal to start solely for sleep.

Higher-risk options (use sparingly, if at all)

Antipsychotics (haloperidol, quetiapine, olanzapine, etc.)

Widely used for agitation and delirious behavior in the ICU; increasingly used off-label for sleep.

Evidence for improving delirium duration or outcomes is weak; evidence for sleep benefit is essentially nil.

Risks: QT prolongation, torsades, EPS, NMS, orthostatic hypotension, metabolic effects.

If used for true dangerous agitation, aim for shortest possible duration and de-prescribe before discharge.

“Z-drugs” (zolpidem, zopiclone, eszopiclone)

Approved for insomnia in outpatients.

In hospitalized/older adults: associated with falls, confusion, delirium.

Worth considering if a home med in a younger person. AASM guideline is cautious about their use.

Antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine)

Essentially using anticholinergic toxicity as a sedative.

AASM guideline also suggests against diphenhydramine for chronic insomnia.

In older adults: confusion, urinary retention, constipation, delirium risk → generally poor choice.

Benzodiazepines

Effective for alcohol/benzo withdrawal and acute severe anxiety, but:

Strongly associated with ICU delirium, especially in older patients.

Profoundly disrupt sleep architecture.

Use only when clearly indicated (e.g., withdrawal), not as routine hypnotics.

System-Level Strategies (“Sleep Culture”)

Add “How did you sleep?” to daily rounds.

Create an ICU Sleep/Delirium Bundle (light, noise, clustering care, pain control, eye masks/earplugs, minimal deliriogenic meds).

Involve nurses, RTs, PT/OT, pharmacists in planning—ask “What can we do tonight to protect sleep?”

Standardize timing of routine labs/meds to avoid 2–5 a.m. peaks in interruptions.

Keep a stash of eye masks and earplugs on the unit; offer them on rounds.